multi-storied #18: A hundred views

At a recent exhibition, Sohei Nishino’s “Diorama Map Tokyo, 2004” occupied half a wall, and it transfixed me. These maps are Nishino’s specialty. From some vertiginous vantage point, he presents a city in what feels like its entirety—not just because of its sprawl away to the horizon, but also because of the life that teems within it. The works are cartographic collages; they’re comprised of hundreds or thousands of tinier photos, each shot from a different perspective and to a different scale, and then artfully assembled into something that feels like a whole. (Nishino: “Perhaps it is the impossibility of capturing the city that is particularly interesing and complicated.”) You can get lost and disoriented the longer you study this collage, as you might in an unfamiliar city. One moment you’re high enough above to see the full, intestinal curve of a Tokyo Metro track, the next you’re right in front of the National Diet Building. The collage is a paradox: it is both a striving effort to encompass everything and a reminder of the futility of any such effort.

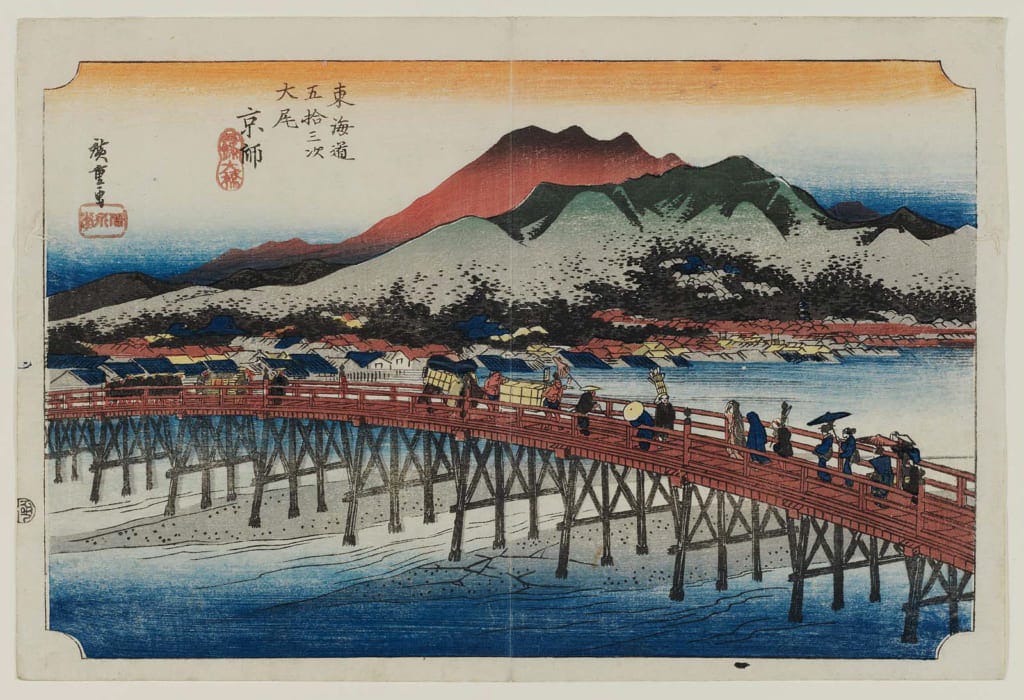

Nishino’s dioramas function, in a way, in the tradition of the ukiyo-e artists of the late 1700s and early 1800s. The paintings and prints of ukiyo-e ran, very often, in series, and their very names declared their ambitions to depict a multiplicity of views—to capture a geographic entity as completely as possible. Witness, for instance, Hokusai’s Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, or Hiroshige’s Fifty-three Stations of the Tokaido, or his One Hundred Famous views of Edo, or Yoshitoshi’s One Hundred Aspects of the Moon, or Eight Views of Omi by Harunobu. Ukiyo-e declined in the late 1800s, but its spirited proliferation of perspectives showed up again and again in the 20th century: in the prints of Koshiro’s Scenes of Last Tokyo or Akira’s New Sights of Tokyo. Nishino’s diorama is merely a consolidation of this rash of perspectives into a single work. It may as well be named Ten Thousand Views of Tokyo all by itself.

This long custom of offering a panoply of views of a single subject fascinates me. It strikes me, of course, that the single subject isn’t really a single subject: that Mount Fuji, for instance, is sometimes just dozing in the distance while Hokusai’s denizens cross the Mannen Bridge at Fukagawa or build a barrel in a field in Owari. The subject becomes an excuse, or a motif. Even so, when these 36 views of Mount Fuji or the 100 views of Edo are summed up, they suggest a vision in completion: the mountain or the city appearing in the fullness of life itself.

The reason behind the production of these numerous views is distinct from their artistic effect. I’d wondered for a while if the ukiyo-e series descended from an older school of narrative painting: the narrative yamato-e scrolls from the 12th century onwards, say, or woodblock illustrations in books. But the truth also seems to be, as the scholar Andreas Marks writes, that the ukiyo-e print was “an urban phenomenon of a purely commercial nature.” The prints were souvenirs, and to issue them as a series—each print marked with a number—was a stroke of marketing shrewdness. Customers loyally tried to collect all the views of Mount Fuji or the Tokaido. They were the baseball cards of their time.

But the neat entrepreneurial opportunism of these series needn’t deter us from marvelling at them—or from finding them significant and moving. Even those of us spoiled by the detail of 21st-century graphic novels must be floored by the richness of Hiroshige’s Cherry Blossom on Nakanocho Street in the Yoshiwara Quarter. The individually patterned kimonos! The careful depictions of class! The exploding cherry blossom, looking like the inside of a lung! The beauty of Hiroshige’s attention is almost staggering. One print, titled Mariko Station, is so fine that we know what soup two men on a bench are eating: tororo soup, made out of mountain yams.

The term “ukiyo-e” translates into “pictures of the floating transitory world,” a reference to the Buddhist notion that our physical world is fleeting and even illusory. To focus on the material, as these artists did—on the soup, or the texture of silk, or the customer walking to the brothel, or the play in the theatre—feels at first like a rejection of that notion. But in totality, all those views of life added up, it turns into the opposite: a celebration of the transitory, an insistence on savouring the world, a rejection not of Buddhist principle but of the grimness of death.

In a 1661 novel, the writer Asai Ryoi wrote: “Live for the moment, look at the moon, the cherry-blossom and maple leaves, love wine, women and poetry, encounter with humour the poverty that stares you in the face and don’t be discouraged by it, let yourself be carried along on the river of life like a calabash that drifts downstream, that is what ukiyo means.” These artists looked and looked again at the moon and cherry-blossom and maple leaves, at mountains and bridges and people, in as many different ways as they could conceive. In this impulse to keep looking, we can find a permanence in an impermanent world.

My last newsletter, about 81allout’s republication of Mike Marqusee’s War Minus the Shooting, prompted all sorts of lovely email from readers who remembered the 1996 World Cup. It was also a salutary reminder to me that errors can sidle into any passage of writing, even if you, the writer, are setting down events you think you’re intimately familiar with. Three small errata in that newsletter, to wit:

Liz Davies was Mike’s partner; they were never married.

It was Penguin Books UK that told Liz they weren’t planning a 25th anniversary edition of the book, not Penguin Books India.

Gideon Haigh offered the foreword himself, unasked—which is even more remarkable!

In a welcome development, the Bangalore bookstore Atta Galatta has stocks of the paperback and are happy to courier copies to other Indian cities if you write to thebookstore@attagalatta.com. They’d laid on some of these copies at the Bangalore Literature Festival this past Sunday, their red spines flashing and bold like Aravinda’s bat. On the same day, the writer Suresh Menon wrote a splendid cover essay about War Minus the Shooting in The Hindu. If you still haven’t bought holiday presents—or even if you have!—this book is calling out to you.