multi-storied #29: War by other means

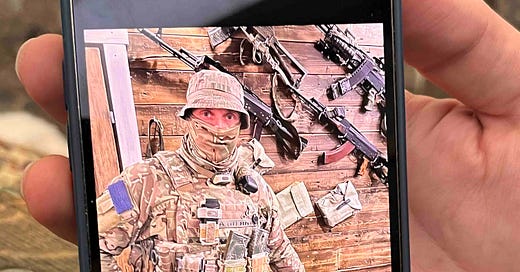

(A word about the image above: The phone belongs to Andrey Liscovich, about whom more below. We were in the German town of Kassel, at breakfast, roughly four months ago. He pulled out his phone to show me a number of photos, including this one, of a Ukrainian soldier with a Skydio drone—a drone that you or I can purchase off the shelf. The image stayed with me. You see nothing really of the soldier except the eyes. He is standing next to a small Texan home’s worth of weaponry, mounted on the wall behind him, but his hand rests proprietorally on his new drone. His eyes seem, to me, tired but also so pleased, as if he is smiling beneath his balaclava-mask. He reminded me of an eager student who’d been gifted a new notebook, and who was already making plans in his head about how to use it best.)

In the flood of horrific details from Gaza, one stuck out. During their Oct. 7 attack, Hamas’s militants wore GoPro cameras to capture footage of their atrocities.

I don’t know if I’d have ordinarily paused at this. Certainly the sudden mention of this benign consumer product, designed for recreational bikers or roller-coaster riders, amidst the discussions of deadly war feels jarring and discordant. (Let us suspend, for a moment, larger arguments about how consumerism and war are intertwined.) I imagine the frontline of war to be such an alien place, so absolutely unlike anything from my own daily existence, that it’s fantastic to contemplate some material things being common to both spheres. This speaks, I am sure, to my ignorance of wartime realities, but I can only be thankful for that.

But the GoPros stood out to me because of a piece I’d published very recently, in WIRED, about Liscovich. Broadly, the piece was about how, like GoPros, other kinds of “civilian” devices are now so sophisticated and so cheap that armies (and militants) can make great use of them. This wasn’t always the case:

A few decades ago, defense researchers built shiny new things—GNSS, for instance, and Arpanet, a precursor of the internet—and eventually bequeathed them to the general population. Now, Brown said, commercial companies are faster and can develop consumer products so cutting-edge that armies would do well to use them. It isn’t just that defense departments move ponderously; the private sector is also awash in far more money. “If you go back to 1960, the military was 36 percent of global R&D spending,” Brown said. “Today it’s barely more than 3 percent.”

Over the past 18 or so months, Liscovich, a Ukrainian tech entrepreneur, has become the Ukrainian army’s personal shopper for these kinds of products. He’s a strange, liminal figure produced by a novel sort of conflict. He is a civilian neck-deep in military work, a Silicon Valley emissary to battlefields beset by electronic warfare, a Thomas Friedman character cast into a Joseph Heller world.

He deals only in nonlethal equipment—merchandise that’s available off the shelf to everyone, or at most classified as “dual use,” suitable for both military and civilian applications. Generals and brigade commanders tell him what they need, and he roves the global tech souk, meeting manufacturers and inspecting their products. Then he cajoles wealthy friends or friendly nations to foot the bill and arranges for the matériel to be fetched to the front. In the year and a half since Russia invaded, he has wrangled everything from socks to sensors to Starlink terminals.

The full WIRED piece is about Liscovich himself, who is a fascinating figure…

To the extent that Liscovich is based anywhere at all right now, it is in a hotel in Zaporizhzhia, where he rents two rooms—one for sleeping and another for working. The building is ugly, he freely admits. He has to use a portable heater in the winter, and summers are so sweltering that he works at night with the windows open, ignoring the gnats and flies that stream in. When Zaporizhzhia was being heavily bombarded last fall, Liscovich moved to a neighboring village, where he slept on hay in the cellar of a house. He still keeps his apartment in San Francisco’s Chinatown, although he spends barely two weeks a year there now. Sometimes he flips open an app and looks at his bedroom through a webcam: the bed made, the blinds drawn, the black-and-white image giving nothing away about whether it is night or day on the other side of the world. He’s a man laboring for his homeland without any real home of his own.

…and about this pattern of use of civilian tech in modern warfare. It may seem like Hamas’s GoPros confirm that pattern, and that this kind of access to such easily purchased materiel confers some sort of parity between the two sides fighting an “asymmetric” war. But that assumption would be a mistake, as Steve Biddle, a defence policy scholar, told me. Sure—in the fear and shock of the first few months of the Ukraine war, “speed was paramount,” Biddlesaid.

Any technology, procured in any way at all, that kept Ukraine in the fight for another day was welcome. But coordinating artillery strikes over WhatsApp and Signal, for instance, was hardly ideal. “Over time, I’d still be concerned about hacking and security,” Biddle said. Similarly, the rate at which Ukraine has lost its off-the-shelf drones has been staggeringly high, he said—between 1,000 and 10,000 a month. While that damage was once tolerable, it has felt increasingly inefficient as the military digs in for the long haul.

Besides, non-lethal tech is still only non-lethal tech. The things that actually win wars are, tragically, those designed to kill human beings. And in that aspect of asymmetric war, there is no parity, as Israel’s bombardment of Gaza shows every day.