Bless the Americans and their complete, almost gleeful devotion to litigation. Among its consequences is the fact that court documents and trial exhibits of every kind are open to journalists who wish to consult, quote, and write about them — something that is not always the case in the UK. (The byzantine British system involves reaching out to a handful of licensed agencies and paying them a very steep fee to get transcripts of what was said in court, or wheedling documents out of case lawyers. Many documents are not public record by default.) Even sitting in London, I was able to get my hands on this:

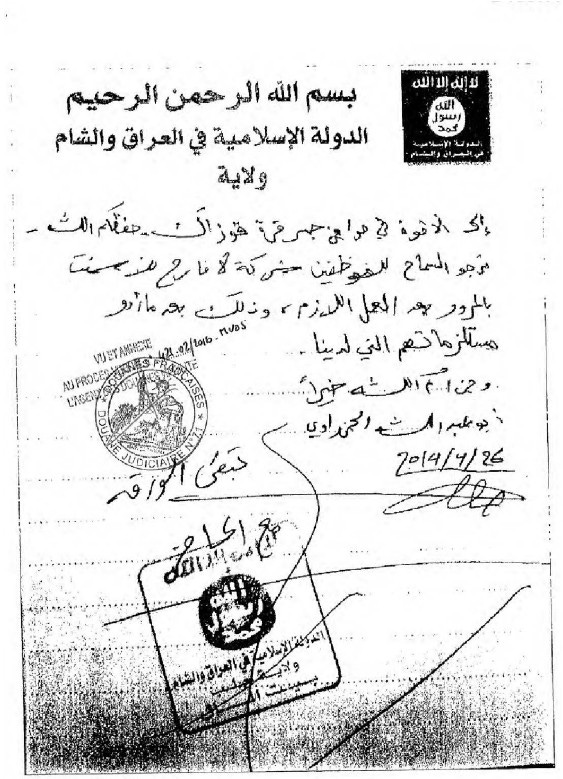

Let me explain how surreal this little document is. It is a vehicle pass, issued in April 2014 in northern Syria. It bears the stamp and letterhead of ISIS. The text, in rough translation, instructs ISIS militants at roadblocks to let the driver and his truck through. The pass identifies the bearer as a driver for Lafarge, the French cement conglomerate, and it says that the company has “fulfilled their dues to us.”

The vehicle pass features as a small element in an article I wrote for the Guardian Long read, published a couple of weeks ago. There were so many reasons, as a journalist, to be drawn to this story. It was about a mutilbillion-dollar Western corporation and its decision, in 2012-2014, to pay ISIS and other militant groups so that it could keep making cement in Syria. But this wasn’t just protection money; MBA jargon, the company optimised for ISIS. Even as its European executives left the country, its local employees got kidnapped, and bombs and gunfire tore up the region, Lafarge bought raw materials from ISIS-approved vendors, supplied ISIS with cement, and paid them to squeeze the competition — in this case, cement imports coming over the border from Turkey:

The managers in Lafarge’s Syrian subsidiary knew all too well what they were doing, and they tried hard to hide it. Once, while referring to vehicle passes that IS issued Lafarge’s trucks, [the CEO Bruno] Pescheux emailed a go-between to say that “the name of Lafarge should never appear for obvious reasons in any document of this nature. Please use the words Cement Plant if you need but never the one of Lafarge.”

This was such a moral travesty that it begged to be written about in detail. And Lafarge itself, and the cement business at large, intrigued me. Concrete, made out of cement, is the second-most consumed material in the world after water, but we don’t know nearly as much about it as we should. Lafarge has been a typically, ruthlessly extractive company. “It was the highest-paying cement company: business-class travel, five-star hotels,” one former executive told me. “For a guy like me, being given an Amex card with a $50,000 limit, and being told that I can use it for whatever I wish, as long as it’s not personal expenses – well, it was a very good life.” But Lafarge will also quarry limestone in a northeast Indian forest and build a 10-mile conveyor belt to its factory across the border in Bangladesh — over the protests of indigenous communities worried about the project’s ecological cost.

To be honest, though, it was the vehicle pass that attracted me — that and one of the emails that Lafarge received from the militants, which came, according to its signature, from “The Emir of the Investment Office in the Islamic State in Iraq and Sham.” These whispers of mundane bureaucracy in the midst of a roiling conflict zone! How vividly they conveyed the speed with which the abnormal becomes the norm!

I wondered, for a long time, about the Frenchmen taking the bizarre decision to pay off ISIS for the sake of their cement market. When I saw the vehicle pass, I was reminded of the human tendency to become accustomed to even the most outrageous situations — and to do outrageous things in response, as if granted some special exemption or some special invisibility. In Sri Lanka, when I was researching This Divided Island, I ran into this tendency all the time:

Through threats and blows, the state was scraping away at the lives of journalists, fraying them thin. One journalist found that, every time he came out of his house, a helmeted man on a motorcycle was waiting patiently for him; if he wanted to walk to the bus stop, the motorcycle followed, making no effort to hide itself. ‘The first time, I panicked. Then after two weeks, it felt normal. I learned to look upon him as a faithful shadow.’

Ordinary people became smugglers — even ingenious ones — in the thick of the civil war and its blockades between the north and the south. Sundaram, a mechanic in Jaffna who kept cars alive at a time when no one could purchase new ones, told me:

Occasionally, he asked friends to smuggle things in past the blockade. ‘I’ve had women put piston rings on their babies’ wrists and say that they were bangles,’ he said, snorting with laughter so that some cream soda leaked out of his nose. ‘And they would put petrol into feeding bottles. At the checkpoint, they would tell the soldiers, “I need to feed my baby,” and they would walk away for privacy. So the army wouldn’t check to see what was in the bottles.’ When, late in the 1990s, Sundaram moved to Qatar for a few years to escape the war, he felt maladjusted to a culture of plenty. ‘Sometimes, even if a small part looked like it was mildly flawed, I’d be ordered to replace the whole thing, even though I could have repaired it easily.’ He threw up his hands in mock horror. ‘Such wastage! I couldn’t believe it!’

At the Lafarge plant in Syria, Jacob Waerness, a risk manager, described the situation as the proverbial frog in a pot of water brought slowly to a boil. (He refused to answer my questions, but it turned out he’d written a book in Norwegian about his experiences. So — and here’s a bit of 21st century tradecraft — I bought the book on Kindle and read it with the inbuilt translation feature, which only allowed me to translate one paragraph at a time. Select a paragraph, hit translate, read the English, then select the next one, and so on.) By the end of autumn in 2012, Lafarge’s managers in Cairo, Jalabiya and Paris were dialling into a crisis unit meeting every week. But what an ordinary western company would have “considered a real crisis became, for us, as the weeks went by, something banal, and our tolerance threshold for negative incidents became much higher,” Waerness wrote. The abnormal became normal — and thus implicitly permitted the abnormal. Or so Lafarge must have thought.

Here’s the full Guardian piece again, with lots more detail, including the question: Can you punish a company for war crimes or crimes against humanity? It turns out, happily, that lawyers are willing to try.