With barely a week to go for the new year, a stocktaking is inevitable. I still have an article in at the Washington Post, that I believe will be published before 2024 is out. But that aside, I’ve completed ten pieces and a slim book this year. (The book, to be candid, was begun earlier.) Ten is a nice, round number: one for each finger of the hand, unless you’re Django Reinhardt or Hrithik Roshan. Here’s a round-up of ten things I learned (plus a final bonus one, from the book) this year.

Elephants need to walk to stay well. Often, they will walk more than a dozen kilometres a day, and they remember their seasonal routes through forests and pass them down to their offspring. In an enclosed space, an elephant’s feet will abrade; its posture will deteriorate; its spine and joints will ache. The elephant itself will turn neurotic from being unable to walk. It will rock and sway on the spot, a shrunken echo of its once-regal gait. “Sometimes you’ll see an elephant eat at a place, go somewhere else, and return after a year. They’re creatures of habit.”

(From “What it takes to live near an elephant herd,” the Washington Post, Jan. 21, 2024)

I recognised afresh how complicated Indian voters can be, and how difficult it is to taxonomize them neatly by party ideology. In Amethi, long the pocket borough of the Gandhi family, I met a Congress worker named Sanjay Singh. He wore a shirt and trousers in spotless white, and in the course of our conversation, I found out that he’d carefully digitized old photos of himself with Rahul Gandhi, Priyanka Gandhi, and Sonia Gandhi, so that he could pull them out of his phone’s album at a moment’s notice to show people. He beamed with pride about his Congress connections. We exchanged numbers — at which point I saw that his Whatsapp display picture was of the gleaming, saturnine Ram Lalla idol newly installed by the BJP in the Ayodhya temple, the culmination of a long-brewed Hindutva project. I asked him about it, and he offered a long analysis, the crux of which was: It’s possible to be a Hindu who was staunchly with the Congress but also, with mixed feelings, glad that Ram had returned to Ayodhya. How can any psephologist ever hope to neatly label a voter like that?

(From “Time Is Running Out for Rahul Gandhi’s Vision for India,” The New York Times Magazine, Apr. 20, 2024.)Mark Twain invented a self-gumming scrapbook for authors, into which they might paste notes, newspaper snippets, and images, for subsequent inspiration. (His secretary once filled six scrapbooks with clips about the Tichborne trial in London, involving a no-name butcher who claimed the title to an English peerage. Twain concluded that the tale was too wild to be of use to a “fiction artist”—but it did form the basis of Zadie Smith’s latest novel, The Fraud.)

(From “AI and the End of the Human Writer,” The New Republic, Apr. 22, 2024)In cricket, for batters, the label of being beautiful — or not — sticks. In 1999, in a Test match in Jamaica, Steve Waugh and Lara both hit centuries, but Waugh made his considerably faster. “I remember reading reports of the match, saying Lara scored a graceful, elegant 100, whereas Steve Waugh scored a gritty 100,” Waugh said. It still rankles. “Once you have the tag, it doesn’t change.” The beautiful players feel the pinch, too. “To the detriment of their career, they think they’ve got to play that way all the time,” Waugh said. “Sometimes, if you aren’t in form, you have to get down and dirty and play ugly to survive, to get through it. Some of these players think, ‘Well, I can’t do it, that’s not my style,’ so they play a shot that’s probably not on. They feel they can’t play an ugly innings because people don’t expect that from them.”

(From “The irresistible mystery of the beautiful batsman,” Financial Times, Apr. 13, 2024)The founder of Bellingcat, the foremost cyber-forensic sleuthing agency in the world, spends his spare time fooling around with AI music engines like Suno and Udio. “I like it especially when the AI generator really gets weird, goes completely off the rails,” Eliot Higgins told me. “I write loads of songs about things like filter bubbles online and stuff.” He has a SoundCloud…

(From “How to Lead an Army of Digital Sleuths in the Age of AI,” WIRED, Jun 6, 2024)Only one in 10 of the 2.8 billion people in the hottest parts of the planet have access to AC in their homes. The climate crisis is, for the most part, not of their making — and yet it is now, as temperatures soar in their cities and villages, that bodies like the International Energy Agency are calling for moderation in our reliance on air conditioning.

Perhaps the key to dialing back our air conditioning habit lies not in how many AC units are used but who uses them. Even with global warming, the temperate regions of North America, Europe and Japan can cruise through the better part of their summers with just a ceiling fan. The reward won’t lie only in the fan’s environmental virtuousness, I promise.

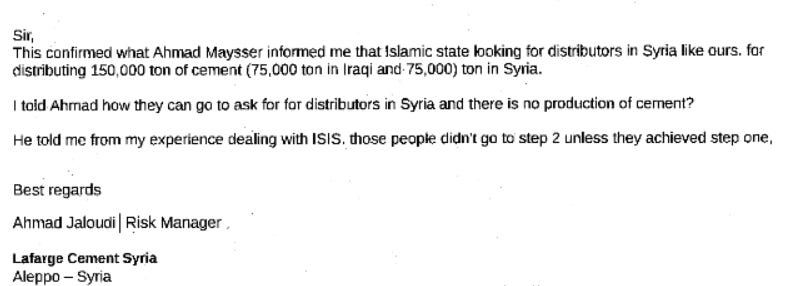

(From “This appliance might be all you need to ditch your AC this summer,” the Washington Post, Aug. 18, 2024)For two years, a subsidiary of Lafarge, the French cement giant, did business with ISIS so that it could keep making and selling cement in Syria. Lafarge bought raw materials from IS-approved vendors, supplied IS with cement, and paid them to squeeze the competition – in this case, cement imports coming over the border from Turkey. In mob jargon, this was more than protection money; in MBA jargon, the company optimised for ISIS. As I investigated this story, I gathered stashes of internal emails and memos of the kind below, in which managers discuss ISIS with each other as if the terrorist group were merely a pernickety logistics provider or tardy supplier.

(From “The cement company that paid millions to Isis: was Lafarge complicit in crimes against humanity?” The Guardian, Sep. 17, 2024)

Alfonso Cuaron, director of the film Children of Men has not read the P. D. James book on which it is based. From my interview with him: “I saw the film pretty much as soon as I read a one-page outline of what the book was about. So in that case, I made the conscious decision not to read the book; I didn’t want it to sidetrack me from what I was thinking. People tell me it’s great. But I guess my Children of Men times have gone.”

(From “Alfonso Cuarón Subverted Sci-Fi and Fantasy. Now He’s Coming for TV,” WIRED, Oct. 9, 2024)As sportsbetting moved online this century, customer appetites grew commensurately insatiable. It wasn’t enough to offer prematch odds on an English Premier League fixture and wait for punters to walk up or dial in. To meet the voluminous demand for soccer alone, bookmakers had to start plumbing practically every tier of every league in every country in the world. Then they did the same across dozens of other sports, right down to the manifestly obscure. (Floorball, anyone? Kabaddi? Or the Finnish baseball variant called pesäpallo?)

The work of trawling the sporting universe and calculating this unending torrent of odds is in various parts data collection, statistics, algorithm modeling and artificial intelligence engineering. No sportsbook has the resources to do it all. Instead, they rely on specialized companies that are closer in character to the quants of Wall Street than to the bookies down at the dog track. To these firms, which mostly originated in Europe but now also drive betting in the newly open and wildly lucrative American market, every game is an interplay of statistics. They’re confident that, with enough data, harnessed in deals with sports leagues that reach into the hundreds of millions of dollars, they can set realistic odds for even the most specific of events, such as a goal scored by a midfielder with his head in the last 10 minutes.

(From “Inside the Companies That Set Sports Gambling Odds,” Bloomberg Businessweek, Oct. 11, 2024)In the early 20th century, an Irish opium agent conducted the first (and still so far the still most comprehensive) language survey of India. It was nowhere near complete; he virtually skipped over the south’s Dravidian languages altogether. Still, scholars admire George Grierson’s work for its openness to linguistic variations (or “shades,” as he calls them), its grammatical scrutiny, and its care in laying a base for further scholarship—on how Indian languages ought to be grouped into families, or how linguistic traits have diffused and converged across these families. Indians, for example, share a fondness for “echo words,” such as puli-gili, in Tamil, where puli refers to tigers and gili is a rhyming nonsense term meaning “and the like.” This quirk occurs in South Asian languages from at least three families—a discovery that Grierson’s specimens helped make possible.

In drafting the passage above, I drew on various texts and linguistic journal articles, and relying upon one of them, I initially wrote that “echo words” appear in no other language families elsewhere. The New Yorker’s fact-checkers, ever punctilious, suggested that we cover our bases by saying that echo words occur “perhaps in no other languages anywhere.” As it turns out, Turkish has ’em, as two correspondents wrote to me to point out. “The same phenomenon of ‘echo words’ is found in Turkish as well, for instance: kaplan-maplan (tigers and such), ekmek-mekmek (bread and such), siyah-miyah (black and such),” wrote Omer Egecioglu, an emeritus professor at the University of California Santa Barbara.

(From “Should a Country Speak a Single Language?” The New Yorker, Nov. 18, 2024)And by way of a bonus: a photograph from Abidjan, taken on the very last reporting trip for the new book. Did you know that when a new undersea Internet cable is brought to shore, a cable-laying ship will often back its big posterior back up towards the coast, as far as the water depth will allow? Then a diver or a pair of divers will guide the cable (itself as thin as a hosepipe, but armoured in steel) to the beach, where it will be buried deep by the earthmovers standing patiently by. The final, complex act involves a plough or a jet trencher: a machine that creates a trench in the seabed just off the beach, lays the cable gently down into it, and covers it back up. These trenches extended far off the coast — until the water depth exceeds 2,000 metres or so, and cable companies are confident that a fishing boat or a ship’s anchor cannot damage their delicate undersea infrastructure. And yet: cuts do happen, as I discovered—and more and more often, cutting an undersea data cable is a discreet act of near-war. In the 21st century, there’s nothing like depriving an enemy of the Internet to truly cripple him.