multi-storied #41: What are the odds?

This piece appeared last October in a Bloomberg Businessweek special package on sports gambling—an industry that is rapidly being legalized in US state after US state. In the old world, though, sports betting has been incredibly sophisticated for years, spinning off a whole new sector filled with quant shops. This is is a story about those shops.

Along with the pub and the kebabery, one fixture of nearly every British high street is the betting shop. Even unconsciously, the eye registers the distinct colors of their signboards: the forest-green frontage of Paddy Power, the navy of William Hill, the red-bleeding-into-blue of Betfred, the angry red of Ladbrokes. Since betting became legal in the UK in 1961, these bookmakers have taken hundreds of billions of pounds in bets—not just on World Cups, tennis tournaments and elections but also on when humans would walk on the moon, whether the yeti really exists and how long it would take to recapture an African golden eagle that had fled the London Zoo. Their integration into English life has been so thorough that, during the anti-immigrant riots in the summer of 2024, a man with a sticker reading “British and Proud” on his chest lamented the loss of a country that once had “pubs everywhere, betting shops everywhere.” He said this standing in front of a pub, with two betting shops a 10-minute walk away.

Even though the betting shops are far from extinct, it’s certainly true that, over the past 15 years, much of action has moved online. In parallel, sportsbooks have heavily outsourced what might be considered the nucleus of their job: setting odds for gamblers to bet on. They’ve had to. As websites and apps became the most popular way by far to bet, customer appetites grew commensurately insatiable. It was no longer enough to offer prematch odds on an English Premier League fixture and wait for punters to walk up or dial in. To meet the voluminous demand for soccer alone, bookmakers had to start plumbing practically every tier of every league in every country in the world. Then they did the same across dozens of other sports, right down to the manifestly obscure. (Floorball, anyone? Kabaddi? Or the Finnish baseball variant called pesäpallo?)

Sportsbooks also offer a smorgasbord of odds that change in real time during games, tempting the itchy trigger thumbs that are always poised over our phones. “Bookies need to have something live at any point in time,” one industry insider told me. (Like others quoted in this article, he requested not to be named owing to the secretive nature of the business.) “To not have that would be like”—and here he paused, searching for the perfect analogy and then finding it—“Amazon not having things to sell during some points of the day.”

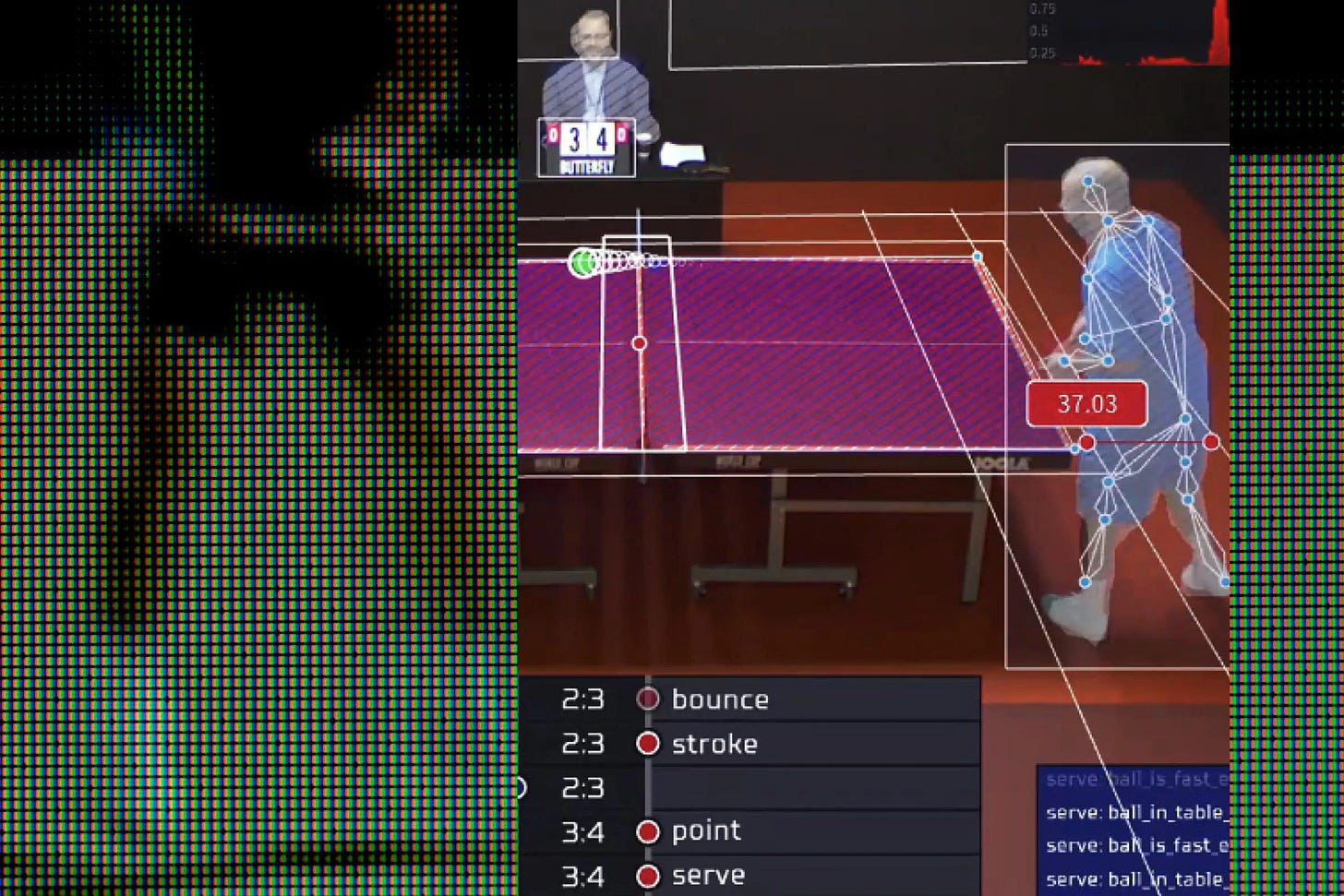

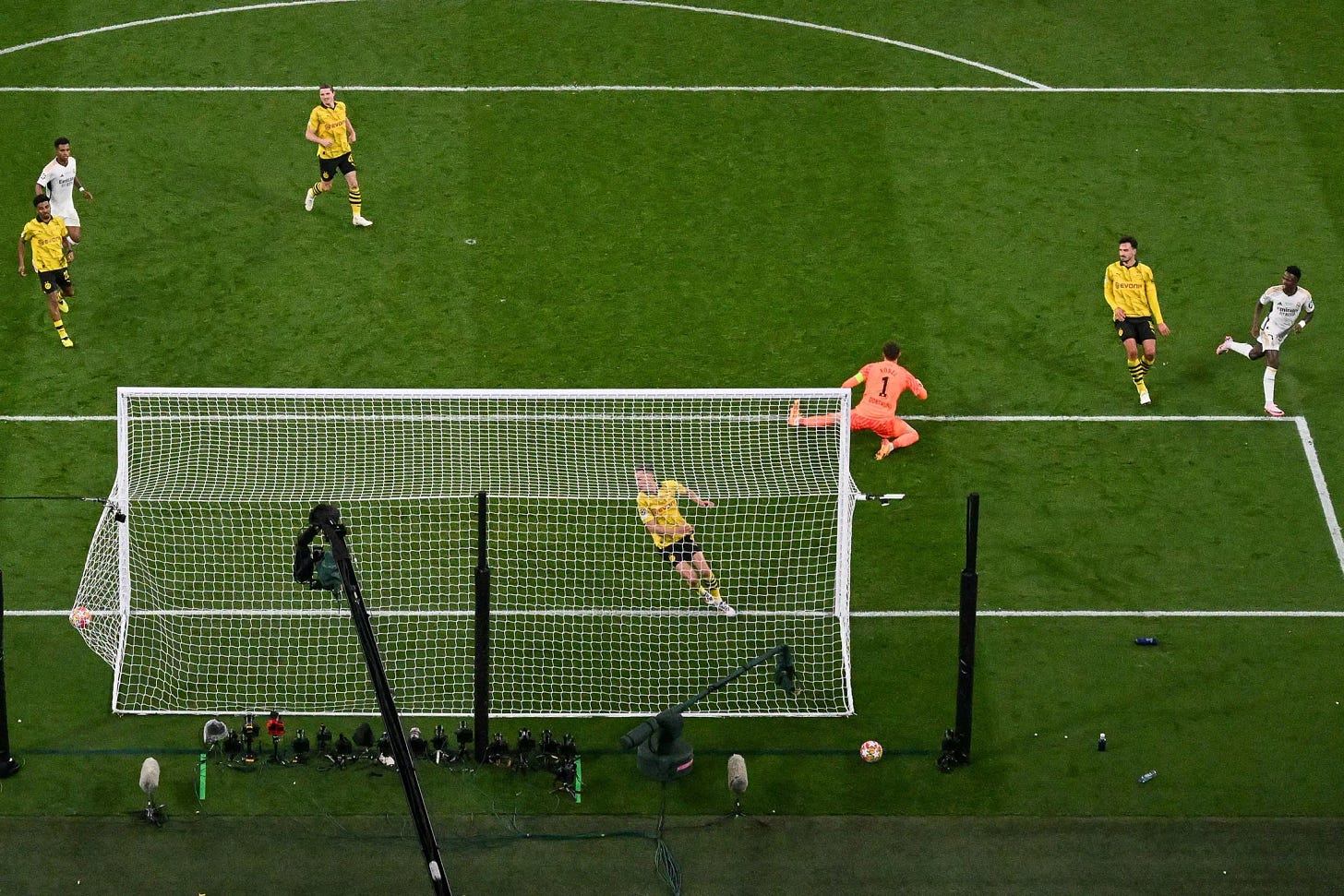

The work of trawling the sporting universe and calculating this unending torrent of odds is in various parts data collection, statistics, algorithm modeling and artificial intelligence engineering. No sportsbook has the resources to do it all. Instead, they rely on specialized companies that are closer in character to the quants of Wall Street than to the bookies down at the dog track. To these firms, which mostly originated in Europe but now also drive betting in the newly open and wildly lucrative American market, every game is an interplay of statistics. They’re confident that, with enough data, harnessed in deals with sports leagues that reach into the hundreds of millions of dollars, they can set realistic odds for even the most specific of events, such as a goal scored by a midfielder with his head in the last 10 minutes.

Then, they can sell those odds. Sportradar Group AG, headquartered in St. Gallen, Switzerland, and one of the largest companies in the field, provides its services to more than 900 bookmakers globally. This past year, it oversaw $40 billion in liquidity—in bets placed with its clients, that is. “Which makes us, from at least a public reporting point of view, the biggest bookmaker in the world,” says Carsten Koerl, the company’s founder and chief executive officer. (“I can’t tell you about the black market, of course,” he adds.)

Sportradar and peers such as Stats Perform, Genius Sports and IMG Arena now do so much of the industry’s core number-crunching that it’s easy to wonder what tasks are left to the bookies besides, well, balancing the books. The biggest operators still do some odds formulation of their own. But Koerl is clear: “A bookmaker is a branding and marketing engine.” The real churn of betting—the pricing of odds, the finessing of risk—happens not in the backrooms of the sportsbook businesses bearing the familiar high street signboards, but deep within the servers of companies that bettors probably haven’t heard of at all.

When Andy Wright, chief betting officer at the sports intelligence firm Twenty First Group Ltd., got his start in the industry, the title “chief betting officer” didn’t exist. In 2006 he left his job at a London fund manager and joined a spread-betting company called Sporting Index, which had a website but only barely. His job involved taking bets over the phone and working out odds for lower-league soccer games. The oddsmaking process began with studying a pile of newspapers for bare statistics: halftime scores, players who’d been red-carded, goal timings. Then he burrowed into internet message boards, where devout fans might offer insights about their team’s performance. Anything for an edge.

Wright’s methods were robust by the standards of earlier eras. One former Ladbrokes employee remembers how, in the late 1990s, one of his colleagues would “make the odds on a piece of paper, then run them to another room, where someone would put them on a screen and send it to the other shops.” Koerl says that, in the early 2000s, some bookmakers sourced tennis odds from a former Czech player, who sent in his verdicts via fax machine.

Wright turned himself into something of an expert on obscure matchups like Stevenage versus Peterborough United, but he was still listening keenly to his gut. When you toss a coin, the odds of it coming up heads or tails are always 50-50. But sport isn’t coin-tossing, and what Wright and others were assessing, in effect, was if one side of the coin was heavier—if the odds really ought to be 52-48. “You look at the scoreline of the last Stevenage-Peterborough game, and you see that Stevenage won 1-0,” Wright says. But that isn’t the whole picture. “Maybe the managers of both teams said Peterborough had more ball possession, or a key Peterborough player was injured, or the Stevenage goalie was unexpectedly amazing on the day.” When the teams played next, a smart bookie—the betting world’s value investor—would take such details into account and offer even money or perhaps declare Peterborough the favorite.

Scavenging those details was a scattershot affair, though. And the limitations were all the more apparent as the number of sportsbooks multiplied and they all sought to exploit the internet’s huge potential for live betting by adjusting odds throughout the course of a game. In the UK, between 2001 and 2004, “there were so many online bookmakers springing up that you couldn’t get to the letter ‘b’ in the alphabet without running into 20 or 30 of them,” says Andrew Cox, the co-CEO of a sports data company called Twenty3. Their backroom pundits lacked a systematic way to find out in real time if, say, the Stevenage goalkeeper was making saves at a higher rate than he usually did. To offer live odds, they needed live data—and lots of it.

An early solution was to rely on people in stadiums, not unlike the ones who’d long sent in statistics and results for newspapers to print. In fact, with mobile phones becoming more common, the cost to bookmakers of not having eyewitnesses escalated. The former Ladbrokes staffer remembers an episode in which one gambler kept beating the house on Real Madrid games. “He was always betting that a goal would be scored just ahead of it actually happening,” the staffer says. “At first we thought, ‘God, he’s a genius!’ Then it turned out he was sitting in the press box in Madrid, placing bets, while we were trading off a television feed that had a 20- or 30-second delay.”

By the mid-aughts, new companies like RunningBall and Sportradar were sending data scouts to games, paying for their ticket and adding a fee of around €100 ($110). Sometimes the purpose was archival. The scouts would record yellow cards and goals in soccer or double faults and aces in tennis to be analyzed later by quants who built computer models to formulate odds. (Somewhere in a soccer museum in England, Wright has seen a scout’s game summaries written in shorthand over a continuous stream of toilet paper.)

Live wagers were catnip to bettors, something Sportradar’s Koerl had found out in the late ’90s while he was running a bookmaking venture called betandwin (later Bwin). During an Australian Open tennis match featuring Boris Becker, his staff forgot to close bets when play began, only to see activity surge tenfold. It was a mistake but an enlightening one.

Sportradar started with a platoon of 50 or 60 scouts, and since mobile internet wasn’t stable enough, each scout sat before a push-button phone. The phone connected to a server that interpreted specific tones as data—as events in the game. “You click on ‘1’ for ‘ball possession home team,’ ‘3’ for ‘ball possession away team’ and so on,” Koerl says. “It works in every different language, in every country.” (A few of Sportradar’s 12,000-odd data scouts still use this system today.) Depending on people wasn’t always failsafe. Sometimes a scout took the fee, stayed home and listened to the game on the radio, Koerl says. “We learned to figure this out by turning on the microphone on their phone.”

Two former scouts described their experiences to me. They’d started in tennis around 2008, armed with HTC Touch smartphones that caught erratic mobile data signals. They could always recognize other scouts: men, for the most part, who sat away from others, trying to keep their hands out of view, never getting up for a drink and never clapping. “Sometimes we had six matches, one after another,” one scout says. He got sunstroke at Indian Wells, an annual tournament in California, and, unable to leave the match he was scouting, had to vomit discreetly into a glass.

There’s much more in the piece: scout terrorism at Wimbledon, nine-figure deals for data rights, the Poisson model that calculated how many Prussian soldiers were killed by horse kicks, Malawi’s football league, AI, and the philosophical conundrum of whom a sports data point — a goal scored, or a double fault — belongs to. Click here to read the whole thing.