multi-storied #6: Will you ever fly again?

In September, after months and months, I took an international flight again: London to Florence, two-hours-and-a-bit, the kind of low-cost hop that so many of us have gotten used to booking. Last year, airlines sold 4.54 billion tickets, and often, it seemed as if all those passengers were in the airport with us. But Gatwick and the Florence airport in September were different: utterly, almost tragically desolate. For the first time, I could see the exposed bones of the industry and understand flying as pure infrastructure. The ranks of check-in desks with no one behind or in front of them. The terminal, suddenly rendered vast by its emptiness. The vacant departure gates that had suffered the amputation of their jet bridges. From entering the terminal to re-lacing my shoes after security check, it took about 8 minutes. Most of that time was needed to fill out a Covid-19 form.

In a new Guardian Long Read, I pointed out:

Among all the industries hit by Covid-19, aviation suffered in two distinct ways. Most obviously, there was the fear of contagion. No other business depends on putting you into knee-by-thigh proximity with strangers for hours, while whisking potentially diseased humans from one continent to another. Less directly, there was the tumbling economy. It is an axiom in aviation that air travel correlates to GDP. When people have more money, they fly more. But in the midst of this historic downturn, no one was buying plane tickets.

This piece had an odd beginning. I’d started talking to several airlines — including KLM, which features heavily — back in February-March, wondering whether I could write something about aviation’s battle to draw down its emissions. The word “flygskam” was being mentioned a lot: “flight shame,” which at least in Europe was inspiring a few people, here and there, to fly less. Then Covid-19 killed that story and replaced it with another. I wanted to find out what airlines do to survive when their planes can’t fly, and what the future of flying even is.

I learned so much: about fuel efficiency, Rasm-Casm, hub-and-spoke models, pricing algorithms. And the pandemic stories from within a major airline like KLM were just incredible. The planeload of passengers, heading to Beijing, finding out that the rules for arrival into China had changed while they were mid-air. The influx of planes into “boneyards” — huge storage facilities for planes, where they’re arranged on paved lots outdoors, looking from the air like the bleached remains of some long-forgotten skeleton. And this tale, told to me by Ton Dortmans, KLM’s engineering chief, who was talking about the planes in hibernation at Schiphol Airport in Amsterdam:

Every seven days, someone would climb into the plane and run the engines for 15 minutes to keep them functional. The air conditioning was switched on to keep the humidity at bay. “And the tyres – well, it’s the same as a car. If you keep a car parked for more than a month, you get flat tires,” Dortmans said. So a tug pulled the plane forward and back every month, to keep the wheels and axles in shape. Still, there were some surprises. In the absence of the roar of jets, birds began to appear around Schiphol again, and one day, a ground engineer told Dortmans that he’d found a bird starting to nest in a cavity in the auxiliary power unit. “I’m hearing all these birds and now I find this,” he told Dortmans. “It feels like I’m out in the woods.”

All this and more here.

We flew back, incidentally, into Heathrow. Where the immigration queue was so long that it took my wife three hours to clear it. Some things never change. Even if, in some apocalyptic future, no one can ever fly anywhere again, I imagine there will still be 450 people standing in front of Heathrow’s immigration desks at any given moment in time.

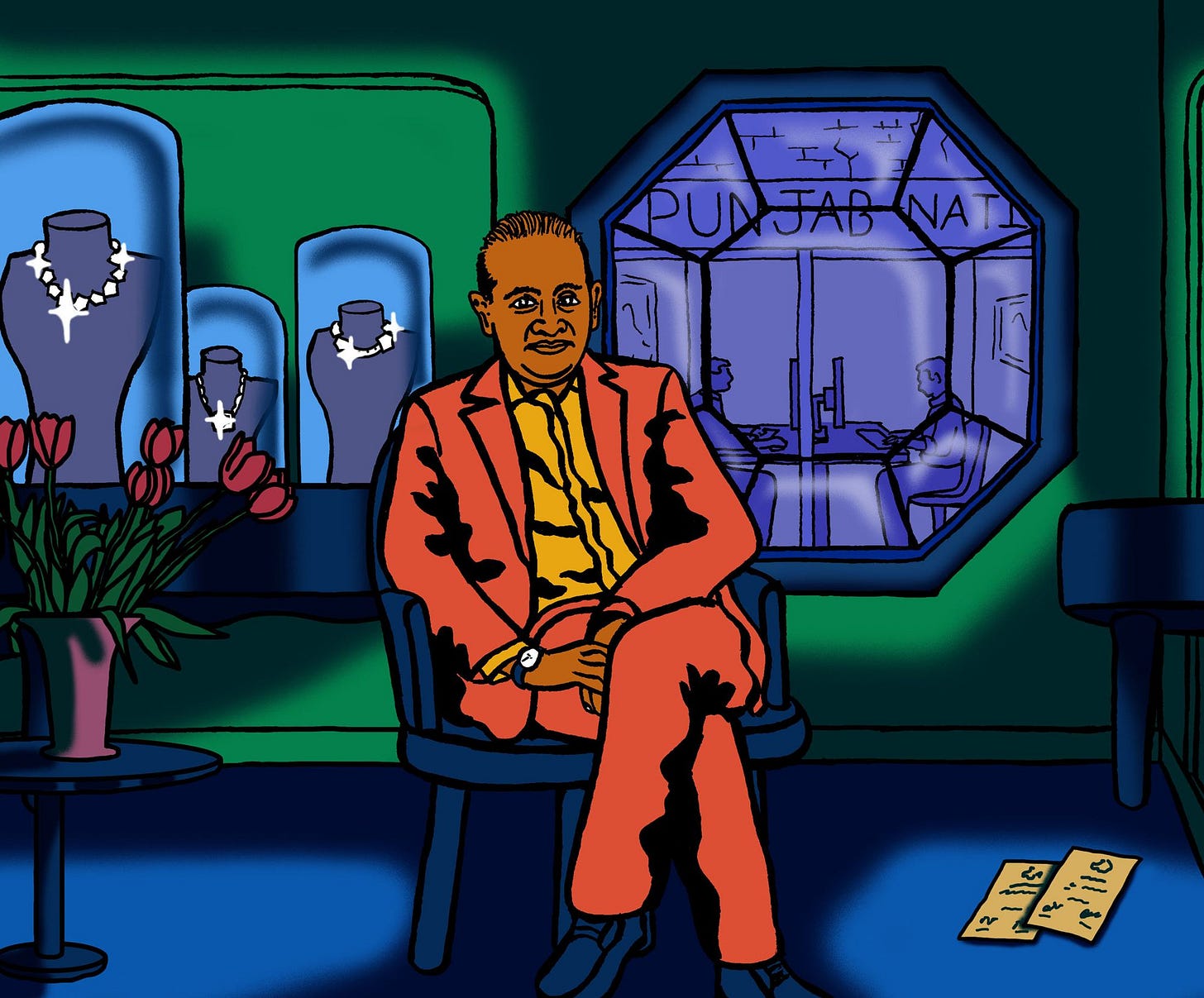

On Netflix, a new docu-series called “Bad Boy Billionaires” has an episode about the absconding billionaire jeweller Nirav Modi. You’ll find me pontificating, thanks to a story I wrote years ago about Modi and his big bank swindle. The show’s release has been on hold for a while because of lawsuits filed by a couple of the other crooks, but Netflix lawyered up and got three of the four episodes out last weekend. My fellow journalists Raghu Karnad and James Crabtree make similar talking-head appearances in the episode about Vijay Mallya, the beer magnate who bankrupted his airline and also fled India, also to London.

When I was reporting my Modi piece, back in 2018, someone told me about her first meeting with him:

During her job interview in his art-filled office, she recalls, he pointed to a poster on the wall—one of the tiny-lettered kind that compress a book’s full text into an image—and asked her if she knew what it was. “He made me get up to go look at it,” she says. When she recognized it as The Count of Monte Cristo, he seemed inordinately impressed.

I’d slipped this little story into my piece and forgotten about it. Then, last year, it emerged that Modi had been using the Count’s real name, “Edmond Dantes,” as his own fake identity while living a fugitive in London.

The world is never short of colour.

My friend Rafil Kroll-Zaidi has a superb piece out in Harper’s, which he sent me last night and which I cannot recommend enough: on the psychopathology of self-storage, particularly in the US:

Millennials, it is often reported, are uninterested in their boomer parents’ abundant accumulated possessions. Might this hurt the storage industry? They also have the highest storage use of any generation, with one fifth of households. (Millennials, and city dwellers, are also likeliest to choose the inscrutable survey response of having “personally experienced” “living in their units.”) Another idly theorized threat to the storage industry is the success of Marie Kondo’s book The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up. The idea seems dubious: consumer storage use recently reached 10 percent of U.S. households, and if anything threatens the business, it would be the pandemic, which appears to have spawned vacancies and depressed rents. It is plausible, however, that a number of Americans attempted a Kondo purge—getting rid of possessions that failed to spark joy, often thanking them for their service before relinquishing them—but wound up storing those things. Since Kondo’s sensibility derives from both Zen’s ideal of nonattachment and Shinto’s respect for the animate dignity of the “inanimate” world, it would be an acute irony for these objects to become imprisoned, like the diverse species of Japanese undead, in a state of irresolution.

At one point, Rafil and his partner decide they’ll use a self-storage unit near their house as an extension of their pantry, so that they don’t have to schlep to the store every time they run out of tuna or chick peas. After a while, they decide this is silly and give up the idea. Then, of course, Covid…

Read the whole thing.